It was in 1992 that Bama expressed her anguish of being oppressed through her writing of Karukku. As much as the text is a non-fiction, it can be seen as a semi-fictional autobiography. The narrative flows smoothly, it does not explicitly show much labour invested in recalling instances from the past. Perhaps, it is one of those styles that unconsciously express the fact that the oppression was too much to have forgotten!

Karukku chronicles Bama's life, from her childhood to her early adult life as a nun, and beyond. Bama begins her story by narrating how she witnessed the caste divide in the very setting of her village;

Most of the land belonged to the Naicker community. ... there is a small settlement of ten to twenty houses, known as Odapatti. It is full of Nadars who climb palmyra palms for a living. To the right there are the Koravar who sweep streets, and then the leather-working Chakkiliyar. Some distance away there are the Kusavar who make earthen ware pots. Next to that comes the Palla settlement. Then, immediately adjacent to that is where we live, the Paraya settlement. To the east of the village lies the cemetery. We live just next to that. ... there were streets of the Thevar, Chettiyaar, Aasaari, and Nadar. Beyond that were the Naicker streets. The Udaiyaar, too, had a small settlement there for themselves.

The different castes, as Ambedkar would put it, were divided not by the division of labour, but by the division of the labourers itself. Bama emphasises on this statement, and her text becomes a reflection of a servitude with which her family members were bound to the upper-caste families they worked for.

The story narrates Bama's first glimpses of untouchability, dehumanisation of Dalits and the humiliation that came about with the most trivial practices. There is an incident narrated where some snacks are wrapped in a newspaper and held tight using a string, and the Dalit child is made to carry the parcel by the string embedding the notion of untouchability. To counter this, the only motto Bama is taught by her brother is to be educated. Bama perceives education as an emancipator. But soon, she witnesses the politics that emerge in this institution. While education spaces are supposed to be emancipative - free of all markers of identity and privilege, equalising spaces - these spaces do not emerge like that.

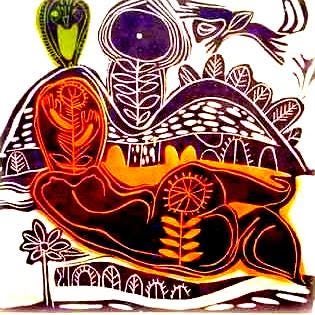

Karukku, as Bama writes, is a book "written as a means of healing (her) inward wounds"; here is a woman who is attempting to make sense of her many identities. The story at large reveals how Bama is exploited thrice (on three levels) - as a Dalit, as a Dalit Christian, and as a Dalit Christian woman. Therefore, Karukku becomes an elegy to the community Bama grew up in - she writes of life there in all its vibrancy and colour, never making it seem like a place defined by a singular caste identity, yet a place that never forgets its caste identity. There is a claim for an identity, but there is a conscious claim for a change in an already existing identity. Perhaps this is the reason why the protagonist remains unnamed throughout.

Bama's Karukku can also be seen as an example of bildungsroman, as the story charts the narrator's spiritual development through the nurturing of her belief as a Catholic, and a gradual realisation of herself as a Dalit - a self-discovery;

I learnt that God has always shown the greatest compassion for the oppressed. And Jesus too, associated himself mainly with the poor. Yet nobody had stressed this nor pointed it out. All those people who had taught us, had taught us only that God is loving, kind, gentle, one who forgives sinners, patient, tender, humble, obedient. Nobody had ever insisted that God is just, righteous, is angered by injustices, opposes falsehood, never countenances inequality. There is a great deal of difference between this Jesus and the Jesus who is made known through daily pieties. The oppressed are not taught about him, but rather, are taught in an empty and meaningless way about humility, obedience, patience, gentleness.

In this quest, Bama documents the rifts between the Christian beliefs and practices. It becomes a struggle between the self and the community, thereby challenging the religious order. As an subaltern text, Karukku critiques the Brahmin (or the upper-class) aesthetics by presenting the Dalit aesthetics. Sathyam (truth), Shivam (holy) and Sundaram (beauty) represent the upper-class aesthetics, while the Dalit aesthetics challenge this by positing - 'untruth' (birth of shudras from the feet of Brahma - varanas), 'unholy' (touch of a Dalit) and 'unbeauty' (lives of Dalits are always in the margins of the village) - as the opposites.

Karukku is both fiction and autobiography. It is a recreation of much of the life that some lived in the village, and it charts the struggles of Bama to find her own identity. The very act of Dalit writing stands in direct opposition to elitist writing in almost everything - motivation and purpose, ideology and aesthetics and in the nature of experiential reality. It is shaped by the absence of power and recognition.

Thanks for sharing add to my TBR