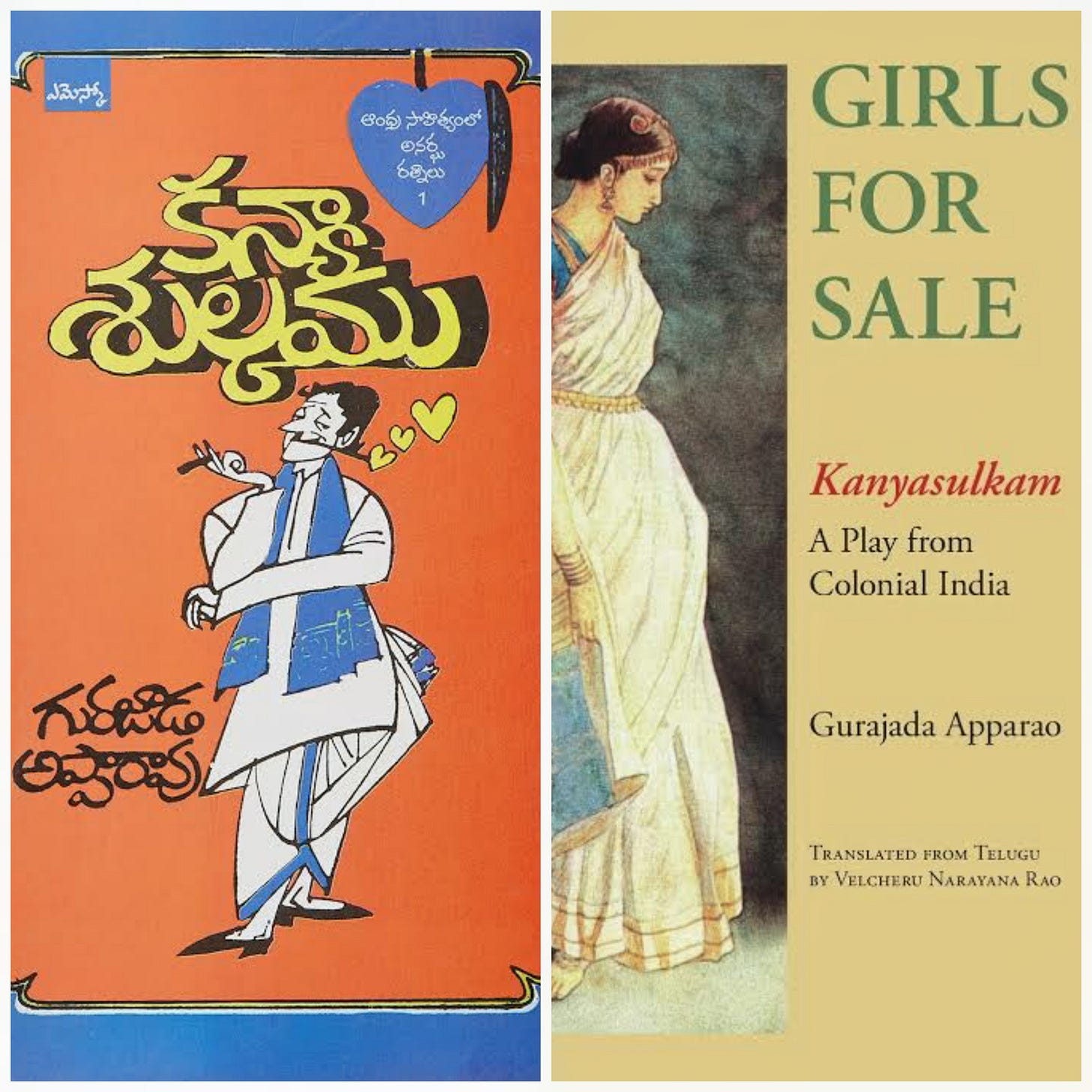

"Kanyasulkam" - The First Realistic Play in Telugu

"Girls for Sale": A Play from Colonial India

(Enter the Disciple at a distance dressed as a religious mendicant boy, singing and playing on a sitar.)

You crave for a house.

Call it your home.

Where’s your home

Little Bird?

RAMAP-PANTULU: Isn’t this my house?

DISCIPLE:

North of the town,

in the land of the dead,

there is a house of firewood,

Little Bird!

RAMAP-PANTULU: In the cremation ground?

DISCIPLE:

You may live long years,

but what’s truly yours?

You can’t take with you,

Little Bird!

Your life of vanity

is lost in reality

Think of the future,

Little Bird!

RAMAP-PANTULU: It really bodes evil, this song.

DISCIPLE:

Fire’s your relative

Wood is your kin.

Who’s your mother,

Little Bird?

RAMAP-PANTULU: Relatives? I really have none. I have a sister; she never comes to visit me. And who is the master of the house anyway? A whore inside and a widow outside - together they drove me out of my own home.

DISCIPLE:

Four people carry you.

A few people follow you.

RAMAP-PANTULU: Stupid song; let’s go. (He walks quickly for a while.) I hear the song even louder. Maybe he is coming this way.

DISCIPLE:

They wait till you’re burned

And turn back home.

No one comes along,

Little Bird.

RAMAP-PANTULU: Crazy song.

DISCIPLE: Pantulu-garu, where are you?

RAMAP-PANTULU: I’d better run or she will catch me.

(Runs off.)

(Curtain.)

The mentioned excerpt capsules the essence of the play Kanyasulkam (kan-ya shoo-l-km), which was written at the wake of the nineteenth century by the Telugu playwright, Gurajada Apparao. Velcheru Narayana Rao has translated this play to English which bears the title, Girls for Sale (2007). The play was first staged in 1892 and was later published in 1897, followed by a second and revised edition in 1909. Kanyasulkam is considered the first realistic play, in any Indian language, which critically reflects on the impact of colonialism on Indian society.

Spread across 7 Acts, Kanyasulkam is a polyphonic play, where each act stands out on its own, yet together they offer a beautifully harmonised melody of a long tale. The play is witty, humorous, serious and devastatingly honest; and the text has been celebrated as one of the classical works of Telugu literature. The dialogues of Kanyasulkam has remained unparalleled:

It has been so popular among educated Telugus that memorized lines from the play are often quoted in conversations. Characters from the play have grown as familiar to people as their next-door neighbours and have acquired a life of their own in the popular imagination.

Kanyasulkam depicts a vibrant upwardly mobile society with people from all walks of life - from Veda-chanting Brahmins to whoring widows, from corrupt police officers to idealistic lawyers, from smart courtesans to pseudo-yogis, from cunning village politicians to dashing English-speaking dandies and intelligent people from a variety of castes and professions.

The play reckons themes such as widow-remarriage, kinship and friendship, corruption in law, gender disparity, the English influence (both the colonials and the colonial language) and rigid patriarchal households. However, I have chosen to elaborate on the theme of colonial modernity.

COLONIAL MODERNITY

Colonial modernity is perhaps more easily defined by what it is not: It is not ‘traditional’. It rejects the immediate past and presents itself as distinctly different from it. In Telugu, the modern poets of the twentieth century present themselves as singers of wake-up songs at dawn, vaitalikulu, implying that they signify the end of a dark night. Navya and adhunika are two of the most prominent words that poets of the early part of the twentieth century loved to adopt as labels for their poetry. Their mode is to reject the establishments of pundits, prescriptive grammars, and puranic themes. In contrast, pre-colonial modernity does not define itself as a radical break with the past nor does deny the significance of the past. It continues the tradition but marks a shift in sensibilities and the way literature is received by the readers.

Kanyasulkam has managed to display an image of an early colonial Telugu world engaged in interfacing with its own residual and emergent worlds. The play discards the old elites (referring to the well-known Brahminic social hierarchy of the four varnas, with its Brahmanas, Kshatriays, Vaisyas, and Sudras - all operating in their distinct spheres); and in its place a new elite has come that is more individualistic and with a new understanding of status and gender relations.

This elite, now the patrons of literature, along with their courtesans, played a prominent role in poetry. The literature of this period began to reflect a new subjectivity that might be called a ‘modern self’.

Apparao’s play speaks about a cultural amnesia that overtook the new middle class, which forgot its immediate past in favour of colonial modernity, which led it to devalue tradition. The new middle class accepted the representation of Indian society as stagnant and decadent and of Indians as a group of people steeped in superstition and immorality, insensitive to human values and incapable of changing. However, Apparao’s creativity to pen sarcastic dialogues lead to an understanding that the society is capable of countering its own problems and mending its own mistakes. Consider the following dialogue:

GIRISAM: You are not a politician unless you change your opinions now and then. Listen to this new argument: There are no young widows unless there are infant marriages. There’s no room for marriage reform unless there are young widows, right? If the test of civilizational progress is widow remarriage, progress of civilization is halted if there is no supply of widows. The civilization cannot go forward even one foot. Therefore we should encourage infant marriages. What do you say? This is a new discovery of mine. Second, I would argue that giving child brides to old men is also desirable. […] Very good. If marriage is a good thing, the more marriages that take place the better, right? Therefore, marry a child bride to an old man and if he dies, to another old man - marriage after marriage and dowry after dowry - in this way a thousand from this man and a thousand from that man and yet another thousand from yet another man - bread on butter and butter on bread - make plenty of bride-money and finally if the woman marries a handsome young man like me - that would be heaven indeed. How does that sound?

It is in this context that we come across the characters in Apparao’s play. These characters are dynamic, enterprising, creative, funny, intriguing, tough, and they seem to be having a good time besides. Apparao is not presenting a society that is deteriorating, nor is it in any moral crisis. And if there is an occasional violation of the moral order, the play strongly suggests that this society itself is capable of setting it right with a strong sense of purpose and determination. Clearly this is not a society in need of social reform. Apparao also suggests, equally strongly, that the impact of colonialism is debilitating even for a confident society such as this one and that the society’s upper castes are losing their fundamental character under the corrupting influence of colonial administration.

While the play in totality sheds light on the attraction towards the pseudo-intellectuals, it cleverly brings in the thought processes of the observants present in the Indian society. Apparao has cleverly roped in the larger pressing issues of caste divide, rift between the Vaishnavites and the Saivites, and the observants v/s the pseudo-intellectuals. Look at the following conversation:

VILLAGE HEAD: Did the earth come first or the sky?

MANAVALLAYYA: Hammer or tongs. what came first?

VILLAGE HEAD: The vertical marks of the Vaishnavites or the horizontal marks of the Saivites - which came first? Hey you, with vertical marks on your forehead, what is my question and what is your counter question? Is the earth the foundation for the sky or the sky the cover over the earth? Those who are learned here, answer my question.

MANAVALLAYYA: The texts say the sky is nothing. That means it doesn’t exist.

VILLAGE HEAD: It doesn’t exist! If you’re blind, it doesn’t exist. You think the white man is crazy? Why does he keep looking at the sky through a tube in the city?

MANAVALLAYYA: How could these impure mlecchas know the secrets of our sastras?!

VILLAGE HEAD: Hey, you with the vertical marks, this is not about chanting allandam bellandam and eating sweet pongali. What do you know about the power of the white man? There’s as much difference between you and the white man as there is between the white man’s liquor and country liquor.

MANAVALLAYYA: In The Texts of Counting, the sky, akasa, means sunya, zero, emptiness, nothing.

VIRESA: The Texts say ‘earth and sky’ - if the earth exists, so does the sky.

VILLAGE HEAD: Ireca, your words are precious.

VIRESA: When it rains hard, people say the sky broke open. If there’s no sky, how could it break open?

VILLAGE HEAD: Hurray, Ireca. Why doesn’t that man with the vertical marks speak up? His mouth is shut.

(Viresa blows the conch.)

This excerpt, in a manner, shows Apparao’s cautioned writing. He does not eulogize the greatness of an ancient India, nor does he see a separate spiritual domain from the political. For him, the entire society is a complex but single fabric that needs to be attended to in all its complexity.

Kanyasulkam was also made into a film in 1955 with the changes a popular Telugu feature film requires, the most notable of which is that Bucc’amma and Girisam are married to make a happy ending.

Well-written post. First book I read (a gift for excelling in studies) and remained my favourite vecer since. The play cuts across times, greed, helplessness, extortion etc., the play is played by many theatre groups, made into movie. Well researched and academic discussions around the play.