Essay on Craft

[2017, Poem by Ocean Vuong]

Because the butterfly’s yellow wing

flickering in black mud

was a word

stranded by its language.

Because no one else

was coming - & I ran

out of reasons.

So I gathered fistfuls

of ash, dark as ink,

hammered them

into marrow, into

a skull thick

enough to keep

the gentle curse

of dreams. Yes, I aimed

for mercy -

but came only close

as building a cage

around the heart. Shutters

over the eyes. Yes,

I gave it hands

despite knowing

that to stretch that clay slab

into five blades of light,

I would go

too far. Because I, too,

needed a place

to hold me. So I dipped

my fingers back

into the fire, pried open

the lower face

until the wound widened

into a throat,

until every leaf shook silver

with that god

-awful scream

& I was done.

& it was human.

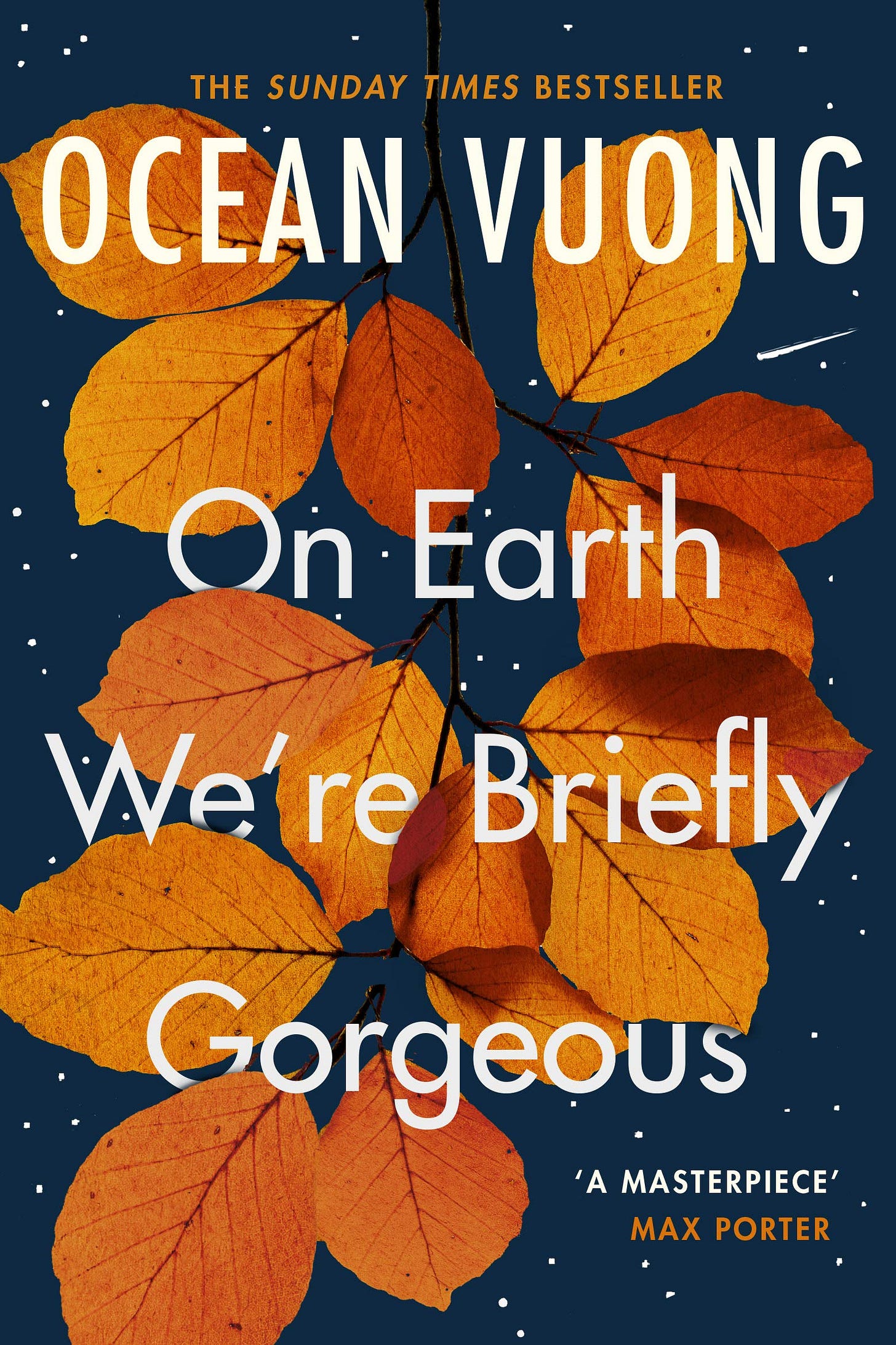

Ocean Vuong, the Vietnamese American poet, essayist, and novelist, has been a ‘must-read’ writer for the brilliance of his 2019 published On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, his debut novel. The writing is raw and strikingly radiant dealing with the exacerbating problems of class, race and gender. Here is Little Dog’s story wrote in an epistolary form to his illiterate mother, where Little Dog hopes that this piece of writing is preserved and that his mother would take birth again only to read his letters.

Raised by an abusive and abused mother and living with a schizophrenic grandmother, Little Dog recounts his rough upbringings while he stayed in Hartford. The very name - ‘Little Dog’ - surrounds itself with a story so compelling that one is bound to comprehend the brutality of reality.

To love something, then, is to name it after something so worthless it might be left untouched - and alive. A name, thin as air, can also be a shield. A Little Dog shield.

Using language creatively, Vuong builds around the fundamental aspect of a problematic relationship that any displaced writer would encounter with “mother tongue”. Often referring to Barthes’s Mourning Diary, he writes:

No object is in a constant relationship with pleasure, wrote Barthes. For the writer, however, it is the mother tongue. But what if the mother tongue is stunted? What if that tongue is not only the symbol of a void, but is itself a void, what if the tongue is cut out? Can one take pleasure in loss without losing oneself entirely?

[…]

Two languages cancel each other out, suggests Barthes, beckoning a third. Sometimes our words are few and far between, or simply ghosted. In which case the hand, although limited by the borders of skin and cartilage, can be that third language that animates where the tongue falters.

Vuong’s way of revealing the brutality of the real world works its way significantly through Little Dog in the form of stories that are fed to him by his grandmother. These stories are repeated over and over, yet, a tiny detail in them told differently brings forth newer interpretations. While, Little Dog tries to fight the seemingly nonchalant evils of race and class, he also has to negotiate between his sexual identity and the non-accepting society. His love towards his partner(s) emulsifies into a philosophy of willing submission and its need in one’s life.

Submission does not require elevation in order to control.

Little Dog’s world is eviscerated of tenderness, and his experience of the war brings him to realise that when tenderness is offered, it remains a proof that one is ruined. The multifarious experiences of abuse compels him to see happiness and sadness as complements of each other.

Do you remember the happiest day of your life? What about the saddest? Do you ever wonder if sadness and happiness can be combined, to make a deep purple feeling, not good, not bad, but remarkable simply because you didn’t have to live on one side or the other?

The metaphors of language and its creativity is poetically discussed which ensues our understanding of ‘freedom’. The work also invites one to think of anger that is just and political, only to camouflage the reality which is artless, depthless, raw and empty.

All freedom is relative - you know too well - and sometimes it’s no freedom at all, but simply the cage widening far away from you, the bars abstracted with distance but still there, as when they “free” wild animals into nature preserves only to contain them yet again by larger borders.

It is the kipuka (piece of land that is spared after a lava flow runs down the slope of a hill - an island formed from what survives the smallest apocalypse) that writes the novel. Bringing in several emotions in the letters to his illiterate mother, Little Dog comprehends that a country is but a life sentence. Beaten up for choosing an opposite gender’s colour - pink, Vuong weaves sorrowful tales through Little Dog that simultaneously bring out the hidden innocence which learns how dangerous a colour can be.